My sixth great uncle Zachary Philip Fonnereau (1706 – 1778) was the sixth of the ten children of a wealthy linen merchant named Claude Fonnereau (1677 – 1740) and his wife Elizabeth Fonnereau née Bureau (1670 – 1735). Both Claude and Elizabeth were Huguenot refugees. Born in La Rochelle, they had came to England as children. Claude and Elizabeth were married in London in 1698.

Zacharie Philippe Fonnereau, born on 30 January 1706, was baptised on 3 March 1706 in St Martin Orgar, a French Huguenot church in Martin Lane off Cannon Street, London.

Like his father Zachary became a merchant. He lived at Leadenhall Street, London and East Sheen, Surrey.

On 13 April 1738 he married Margaret Martyn at Whitehall Chapel, London. Born 23 December 1717, she was the daughter of George Martyn of Oddington, Gloucestershire, and his wife Cary Cave Martyn née Malcher.

Zachary and Margaret had thirteen children.

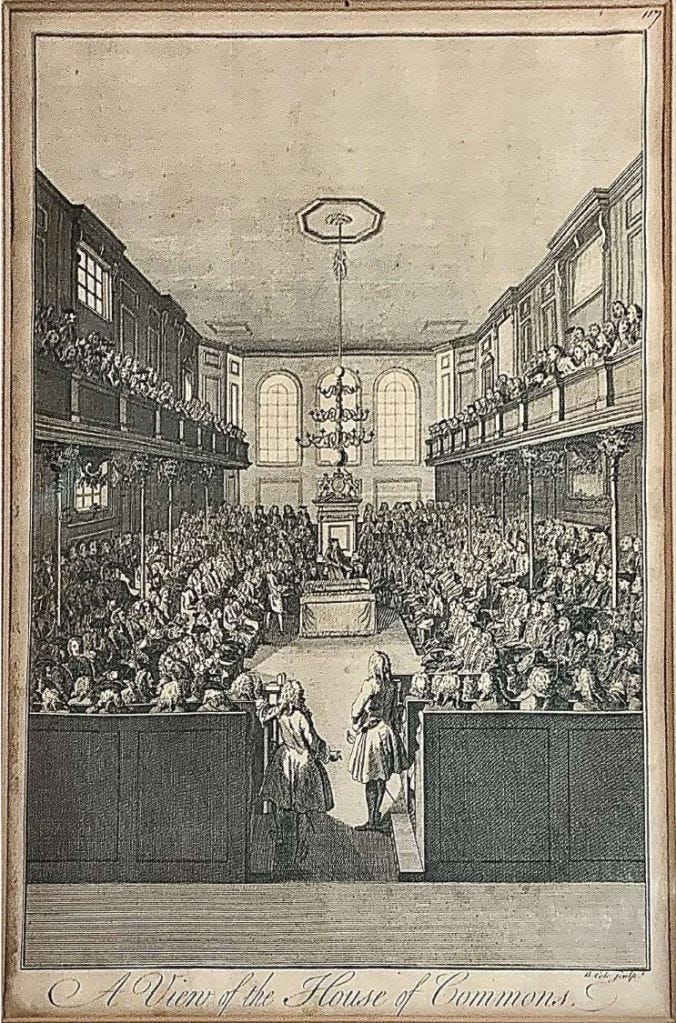

In the 1740s Zachary and his brother Thomas both became members of parliament. The Fonnereaus were associated with two electorates, Sudbury and Aldeburgh, both boroughs in Suffolk. Thomas lived in Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, Suffolk. Sudbury is just over 20 miles west of Ipswich and Aldeburgh is 25 miles to the north-east of Ipswich.

Elections in the 18th century

A parliamentary borough was a town or former town that had been incorporated under a royal charter that gave it the right to send two elected burgesses to the House of Commons.

In the long history of English parliamentary government, constituencies electing members to the House of Commons did not alter their arrangements to accomodate fluctuations in population. In some places the number of electors became so few that they could be bribed or otherwise influenced by a single wealthy patron. In the early 19th century, reformers scornfully called these boroughs “rotten boroughs” because they had so few electors, or “pocket boroughs”, because their MPs were elected by the whim of the patron and so “in his pocket”. The votes of the electors were a mere formality, since all or most of them voted as the patron instructed them, with or without bribery. As voting was by show of hands at a single polling station at a particular time, few electors had the courage to vote against the declared wishes of the patron.

The Reform Act 1832 abolished many rotten boroughs and redistributed representation in Parliament to new major population centres.

In 1872 the Ballot Act introduced the secret ballot, which greatly hindered patrons from controlling elections by preventing them from knowing how an elector had voted. At the same time, the practice of paying or entertaining voters (“treating”) was outlawed, and election expenses fell dramatically.

Between 1715 and 1754 the House of Commons had 558 Members, elected by 314 constituencies. The 245 English constituencies (40 counties, 203 boroughs, 2 universities) returned 489 Members; the 24 Welsh constituencies and 45 Scottish constituencies returned one Member each.

Aldeburgh was a small electorate with only 50 voters. Sudbury was a medium sized electorate with about 800 voters. These boroughs returned 2 members of Parliament each.

The Fonnereaus in Parliament

On 4 May 1741 Thomas was elected unopposed to be one of two members for Sudbury. In about 1749 the 2nd Lord Egmont (1711-1770), described Sudbury as ‘very venal – it may be had by money’. In parliament Fonnereau supported the Prime Minister Robert Walpole.

In 1747 Zachary was elected to represent Aldeburgh. Aldeburgh frequently elected wealthy strangers on the understanding that they would spend money on the borough. Thomas had established so strong an independent interest in the borough that, in the words of the parliamentarian Henry Bilson-Legge, he was able to ‘steal it’ from the Government.

Zachary and Thomas were partners with their fellow parliamentarians Thomas Walpole (nephew of the prime minister) and Merrik Burrell (later a governor of the Bank of England) in a merchant company that held the contract for victualling the Gibraltar garrison.

In 1753 Zachary became a director of the East India Company, succeeding his brother Abel (1703-1753). Abe was a director of the East India Company from 1749 until his death in 1753.

In 1754 a fellow parliamentarian, Brice Fisher, who held the contract to supply cloth for the East India Company, was accused of corruption. When the case against him was brought before the directors of the East India Company, Fonnereau was one of those who took Fisher’s side. Zachary’s directorship was discontinued.

Thomas and Zachary Fonnereau helped finance the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), a global conflict largely between Britain and France, by providing capital and facilitating loans and financial arrangements. During the war, Britain relied heavily on its financial power to subsidize allied armies, especially that of Prussia, and this augmented its comparatively small continental force.

By 1761 Zachary’s son Philip had joined Thomas and Zachary Fonnereau in Parliament. The three consistently voted with the government until the collapse of the Newcastle administration in 1762.

In November 1762 the prime minister Lord Bute negotiated the Paris peace treaty and returned to Parliament determined to have his plans approved. The Fonnereaus initially voted with the opposition, led by the former prime minister, the Duke of Newcastle, against Bute’s so–called ‘peace preliminaries’ but, after Zachary negotiated with the Prime Minister, the Fonnereaus changed sides. Apparently they had little option: Bute and the ruthless Leader of the House, Henry Fox, threatened to remove from positions of power any of the so called Old Whigs who did not vote with them on the issue.

Newcastle condemned Zachary as just another corrupt politician and complained of the Fonnereaus’ disloyalty. However, Newcastle admitted in a letter to Thomas Walpole that Zachary had said to him that “his brother and he had spent thirty thousand pounds in elections; that he had got little from my brother [Henry Pelham, prime minister from 1743 to 1754] and me, and he must look out for his interest”. Indeed, apart from the lucrative Gibraltar garrison contract, Thomas and Zachary seemed to have gained little from their years of voting with the Pelhamites (followers of the prime ministers Henry Pelham and his brother the Duke of Newcastle) and were tired of waiting for a further return on their investments.

After this episode the Fonnereaus returned to their habit of voting with the Government.

In 1768 Thomas stood for Sudbury and lost. Zachary was reelected for Aldeburgh together with Nicholas Linwood, a friend of the Fonnereaus. Five years later in 1773, following the death of Linwood, Thomas was returned for Aldeburgh and remained a member until his death.

Zachary did not stand for the election of 1774. Despite having been a member for 27 years there is no record of him ever having spoken in the House.

Death of Margaret and Zachary and Thomas

On 8 June 1778 Zachary’s wife Margaret died aged 60 “of a mortification in her bowels”. She was buried at St. Peter’s Cornhill. She was just 60 years of age.”

Zachary died soon afterwards, on 15 August 1778, aged 72, and was buried with his wife on 20 August 1778.

On 20 March 1779, less than a year later Thomas died, aged 79, at Old Palace Yard, Westminster. He was buried at St. Margaret’s, Ipswich.

Related posts and further reading

Z is for Zacharie Zachary’s grandfather

B is for beacon the lighthouse at the Lizard built by Thomas

O is for Old Palace Yard: Thomas lived at 4 Old Palace Yard and died there in 1779. As a member of Parliament his London residence was conveniently close to the Houses of Parliament

South from Suffolk to Sussex: we visited Christchurch Mansion in Ipswich which had been bought by Zachary’s father Claude in 1737 and was bequeathed to Thomas

52 ancestors: Whitehall June 15 1727: concerning my 6th great grandfather my sixth great grandfather, Philip Crespigny (1704-1765) who married Zachary’s sister Anne Fonnereau

Philip Champion de Crespigny (1738 – 1803): concerning my 5th great grandfather who was in parliament with his Fonnereau uncles

de Crespigny, Rafe. (2017). Champions from Normandy: An essay on the early history of the Champion de Crespigny family 1350-1800 AD. pp. 171-3

I am very grateful to Steve Hoole who provided me with a copy of his unpublished History of the Fonnereau Family (2002)

History of Parliament online:

Section 1715-1754

Section 1754-1790

FONNEREAU, Zachary Philip (1706-78), of Sise Lane, Bucklersbury, London

FONNEREAU, Philip (1739-97). Zachary’s son, elected 1761 as member for Aldeburgh, his father was the other member

FONNEREAU, Martyn (1741-1817), of Leadenhall St., London Zachary’s son, elected 1779 as member for Aldeburgh

CRESPIGNY, Philip Champion (d.1803), of Burwood, nr. Cobham, Surr. nephew of Zachary and Thomas (son of their sister Anne), elected Sudbury 1774 and Aldeburgh 1780

Wikitree: Zachary Philip Fonnereau (1706 – 1788)

This post was first published at https://anneyoungau.wordpress.com/2025/04/30/z-is-for-zachary/

Your very fortunate to have a Z in your family Anne. I had to look up mortification of bowels. It sounded dreadful to me and I hadn't heard the term. I was interested to read about the English parliamentary system, as I'm shamed to say that I don't know all that much about it and how it has changed over the years. Well done on getting to the end of the Ato Z's again!

Zacharie was named after his grandfather - his father was Claude.

It was interesting to learn how the parliamentary system had evolved - some of the issues of conflicts of interest are still there though. We now change electoral boundaries frequently to try and make sure better representation is achieved.