Contesting the will of W S Chauncy

Continuing Philip Chauncy's Memoir with the death of his paternal grandfather

In 1877 my third great grandfather, Philip Lamothe Snell Chauncy (1816 – 1880), wrote an autobiographical memoir which he dedicated to his oldest son, William Snell Chauncy (1853 – 1903). The State Library of Victoria has a copy.

The memoir briefly describes a court case disputing the will of his grandfather, William Snell-Chauncy (1756 – 1829).

In Nov. 1829 my grandfather W. S. Chauncy died at his seat, Winkfield in Berkshire, my Father being with him at the time. He had, when my Father first married, settled on him a life interest in £16000 the principal to revert to his children they came of age, share & share alike. We also had a smaller recevision [? reversion] in my Stepmother’s settlement of £3,666 which my Father induced his father to make in her favor.

My Grandfather had been very wealthy but had squandered and mismanaged his property, which consisted in slave estates in the West Indies – in Antigua & St. Kitts, landed property in Ireland valued at £10,000 and in England, besides a large property in the funds.

My grandfather was a great tyrant, and on his son’s refusal to learn the business of a West Indian planter (which he did from conscientious motives) he swore he would disinherit him. At his death the bulk of his property passed to other branches of the family, his will was litigated and we found ourselves Wards in Chancery. However each of us recd the 7th share (Anna having died) of the £16000 and of the £3666.

(Prerogative judgment of Sir John Nichol in the cause Westwood v. Burke and others was given on 4th Jan 1832.)

In a memoir of his sister Theresa Poole formerly Walker nee Chauncy (1807 – 1876), Philip wrote that his sister Theresa was “sent on a visit to my grandfather at Wingfield, where she rendered us good service by watching and partially defeating the intrigues of another branch of the family who were using every exertion to obtain an undue share of property from my grandfather in his old age. I think Theresa must have been at Wingfield for several years”. [This would have been in the late 1820s.]

[Her grandfather] William Snell Chauncy was the proprietor of the Winkfield Estate in Berkshire, where he resided for many years ; he was also possessed of slave estates in Antigua and St. Kitts, in the West Indies, of house property in Sackville Street, Dublin, and of considerable funded property.

Her father was his only son, born in London, on the 14th August, 1781, and died at Leamington on 1st August, 1845.

In giving this information, however, Philip Chauncy neglects to mention that his and Theresa’s father, William Snell (Brown) Chauncy (1781 – 1845), was illegitimate, the natural son of William Snell-Chauncy (1756-1829).

William Brown, the son of Eunice Brown and William Snell-Chauncy, was born in London in 1781. He was brought up on the Isle of Man by his mother’s family, with financial support from his father.

On 6 June 1783 William Snell-Chauncy married Sarah Toulmin (1757 – 1834). William and Sarah had two daughters, Sarah (1786 – 1841) and Catharine (1788 – 1858). William Snell-Chauncy and his wife Sarah separated in 1789. The Deed of Separation, issued in 1789, stipulated that William would not have the management of his two daughters.

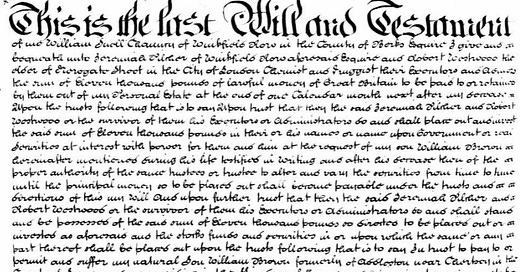

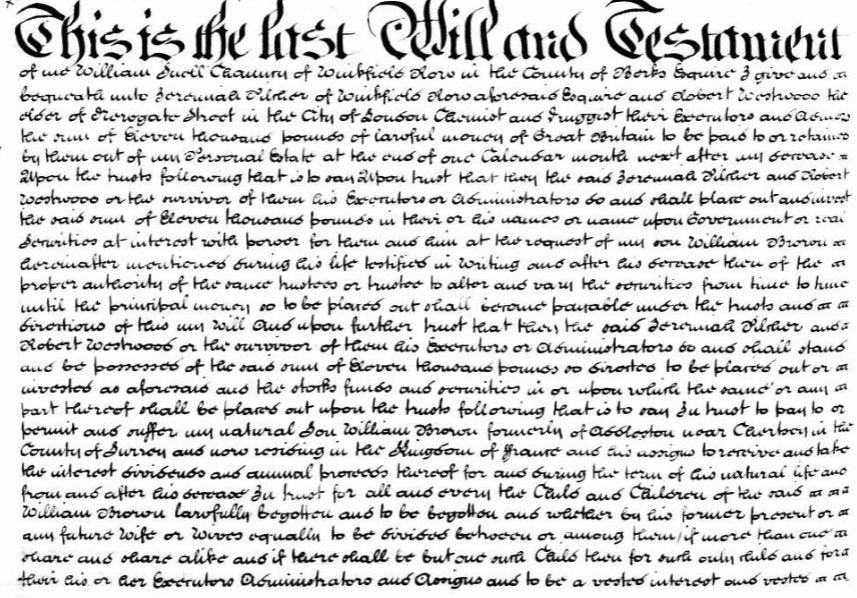

In the will of William Snell-Chauncy senior he named his son as William Brown, later referring to his “natural son William Brown”. The children of William Brown were also provided for, as was Eunice Brown, William’s mother. Only after providing for the Browns does William’s will turn to his daughters Sarah and Catharine. He made no provision for his wife Sarah, stating he had provided for her in his lifetime.

In 1831 William Snell-Chauncy’s daughter Mrs Catharine Snell Burke challenged the legal validity of the will and its codicil on the grounds of the insanity of the testator. One of the executors was a man called Robert Westwood; the case was named ‘Westwood against Burke and Others’. The challenge was put forward in June 1831 and the case came to court in November and December 1831. More than half of William Snell-Chauncy’s estate of £25,000 had been left to his natural son.

The court heard evidence alleging that William Snell-Chauncy’s behaviour had been childish, that he was a habitual drunkard, and that he had conducted himself in an insane and irrational manner. It was also alleged that the signature on the will was not in his hand-writing. The counter allegations were that the deceased, though eccentric, was not of unsound mind; he had conducted his own affairs, had received and paid money, played at cards, spoke French; that he was charitable and benevolent; and that he entertained great regard for his natural son and his family.

On 19 December 1831 The Times reported the proceedings of the Prerogative Court for December 17. The King’s Advocate on behalf of the executors observed that the party opposing the will was really Captain Burke on behalf of his wife and her unmarried sister and that Captain Burke’s difficulty with the will was not that the testator was incapable of making a will but did not make a will more in favour of the legitimate children. The King’s Advocate noted that previous wills made by William Snell-Chauncy in 1799, 1816 and 1820 had all provided for his natural son. Given that the 1789 deed of separation from his wife had stipulated he should not have the management of his two daughters, it followed that there was less intimacy with his legitimate family. But he had had constant interaction with his natural son and his family.

The Times of 5 January 1832 reported the decision of Sir John Nicholl, judge of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. More than 100 witnesses had been examined. There was a larger body of evidence on the case than in any case of the records of the Court. Nicholl found that no act of insanity had been proved and that the whole conduct and history of the testator naturally led to the conclusion of the probability of the dispositions in the will.

Importantly the will and codicil had been prepared by competent lawyers. The Times reported: “The earned Judge then examined the evidence of Mr. Pilcher, the drawer of the will, and of Mr. Horne, the drawer of the codicil, the former of whom, in particular, was an unimpeached witness, and spoke distinctly to the capacity of the testator, and to his perfect comprehension of the act of execution.”

Mr and Mrs Burke were condemned to all costs as it was deemed unfair that the estate should bear any of the costs.

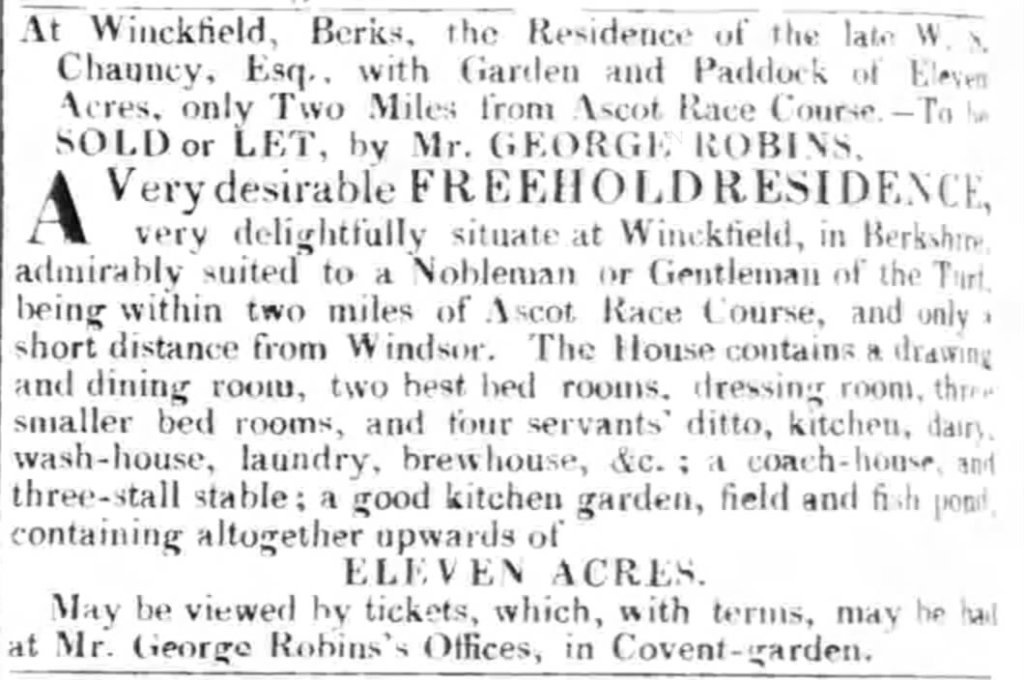

Not long after the will was settled the house of the late W S Chauncy was advertised for sale:

At Winckfield, Berks, the Residence of the late W. S. Chauncy, Esq., with Garden and Paddock of Eleven Acres, only Two Miles from Ascot Race Course.-To be SOLD or LET, by Mr. GEORGE ROBINS,

Very desirable FREEHOLD RESIDENCE, A very delightfully situate at Winckfield, in Berkshire. admirably suited to a Nobleman or Gentleman of the Turf, being within two miles of Ascot Race Course, and only short distance from Windsor. The House contains a drawing and dining room, two best bed rooms, dressing room, three smaller bed rooms, and four servants’ ditto, kitchen, dairy, wash-house, laundry, brewhouse, &c.; a coach-house, and three-stall stable; a good kitchen garden, field and fish pond, containing altogether upwards of ELEVEN ACRES.

May be viewed by tickets, which, with terms, may be had at Mr. George Robins’s Offices, in Covent-garden.

Philip Chauncy was about 15 when his grandfather’s will was subject to litigation. Philip’s recollection that “we found ourselves Wards in Chancery” seems incorrect as there was no reason for the children to be placed under the care of the court. The court case was ultimately successful for Philip’s father for he retained his share of the will of William Snell Chauncy senior. Moreover, that share was contested for it was taken to be the bulk of the estate, this also contrary to Philip’s memory. Philip’s sisters, Theresa and Martha, were witnesses in the court case and were attacked when some evidence was presented to the court. When summing up the judge specifically questioned “the necessity of attacking the character of these two young women? It was an act of justice to them that the Court should declare thus publicly, that the character of these young women had been attacked without any just cause, …”. It would seem that the case would have been very stressful for Philip’s family, not least because they were without an income while the litigation was pending.

Sources

Philip Lamothe Snell Chauncy (1816 – 1880) wrote a memoir of his sister Mrs Poole, Theresa Poole formerly Walker nee Chauncy (1807 – 1876). It was first published in 1873 as Memoir of the late Mrs G.H. Poole by her brother. It was republished in 1976 together with a memoir of Philip’s second wife as Memoirs of Mrs. Poole and Mrs. Chauncy.

Tucker, Stephen, 1835-1887. Pedigree of the Family of Chauncy. Special private reprint, with additions. London: Mitchell and Hughes, 1884. Viewed online at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89062913470 [see printed page 10]

Will of William Snell Chauncy Esquire probated 26 March 1832 PCC Class: PROB 11; Piece: 1795

National Archives PROB 37/883: Westwood v Burke and others Testator or intestate: Chauncy, William Snell formerly of Bishopsgate Common, Surrey; afterwards of Windlesham, Surrey; late of Winkfield, Berks.; esq.

The Times Digital Archive (Transcripts at Wikitree: Prerogative Court Westwood v Burke reported in The Times)

“Prerogative Court, Tuesday, Nov. 15.” 16 Nov. 1831

“Prerogative Court, Saturday, Dec. 17.” 19 Dec. 1831

“Prerogative Court, Tuesday, Dec. 20.” 21 Dec. 1831

“Prerogative Court, Wednesday, Jan. 4.” 5 Jan. 1832

Related posts

This post first published at https://anneyoungau.wordpress.com/2025/01/22/contesting-the-will-of-w-s-chauncy/