Charlotte's Family Bible

In which my third great grandmother attempts to obscure her first marriage

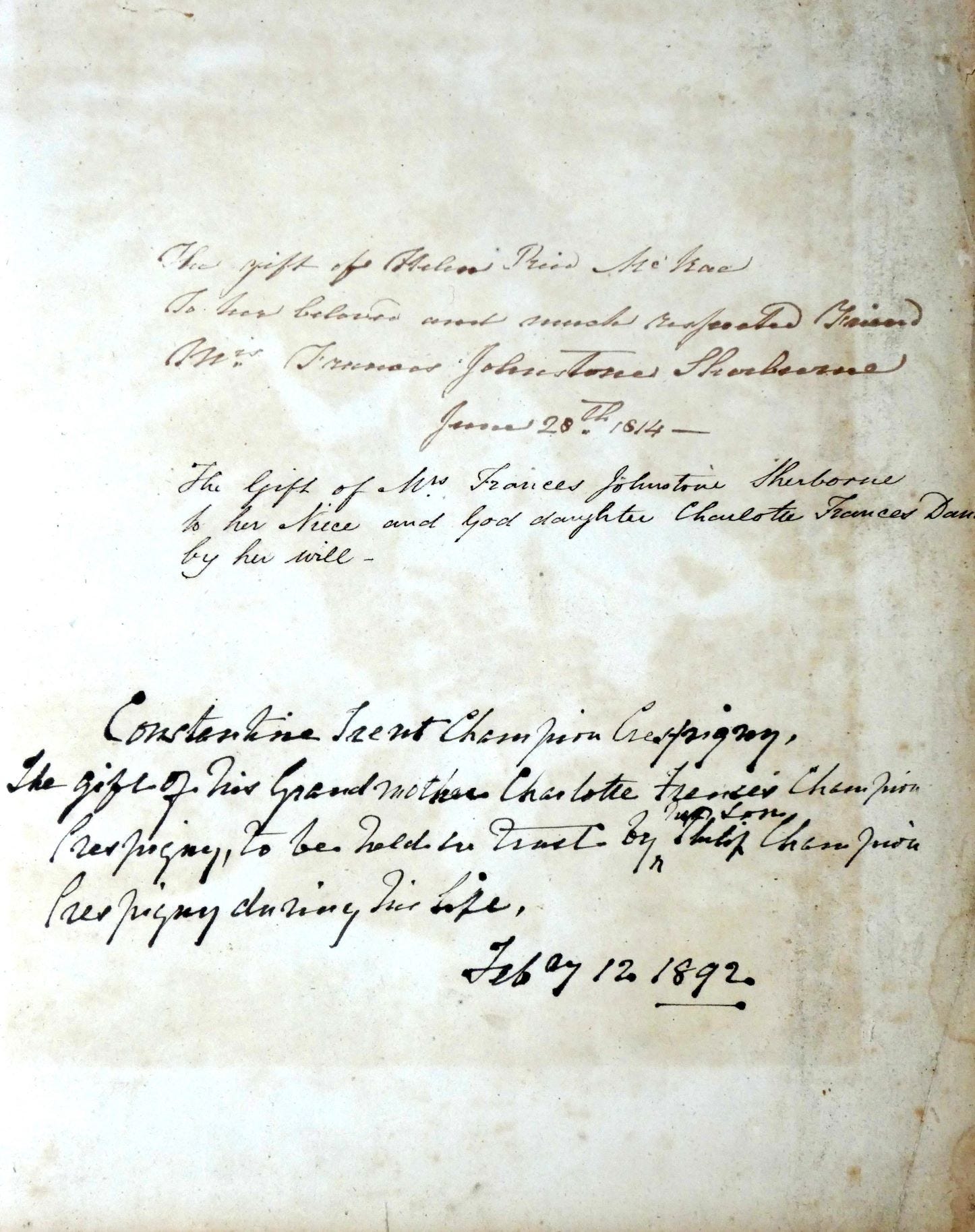

As part of a bequest from her aunt and godmother Frances Johnstone Sherburne nee Dana (1768–1832) my third great grandmother Charlotte Frances Dana (1820-1904) was given a large family Bible.

Twelve inches by fifteen at the cover, and four inches thick, it was printed in London in the early nineteenth century. It was probably originally bound in leather, but has since been rebound in red cloth.

The Bible was given to Frances Sherburne in 1814. It is inscribed:

“The gift of Helen Reid McIvor [Price McRae?] To her beloved and most respected Friend Mrs Frances Johnstone Sherbourne June 28th 1814.”

A second inscription reads:

“The Gift of Mrs Frances Johnstone Sherborne to her Niece and God daughter Charlotte Frances Dana by her will.”

A third:

“Constantine Trent Champion Crespigny, The gift of his Grandmother Charlotte Frances Champion Crespigny, to be held in trust by her son Philip Champion Crespigny during his life, Feb’ry 12 1892.”

Constantine Trent was my great grandfather. He passed the bible to my father.

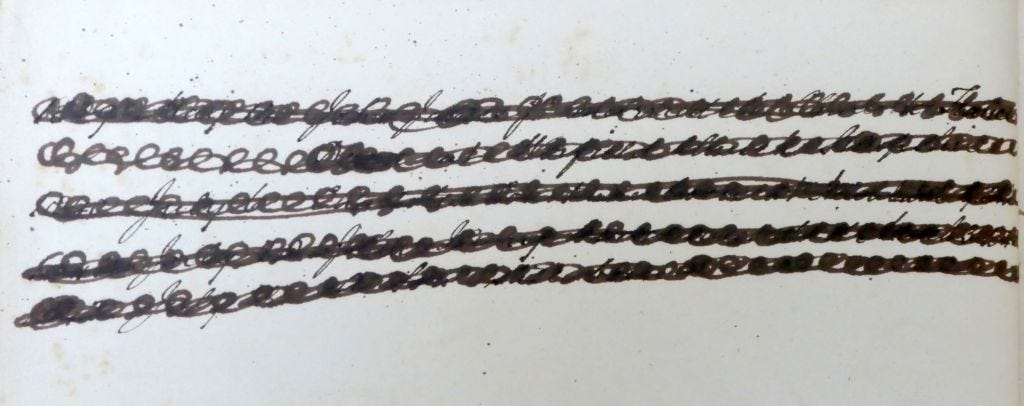

The reverse side of the title page also bears a set of inscriptions. Most of this material was marked over with heavy brown lines to render it unreadable.

With a magnifying glass and strong light, however, much of the first inscription on this page is legible. It appears to have been written by the person who wrote second inscription and, though it was composed some fifty years later, the third inscription, which was signed by Charlotte Frances.

It reads:

1839 May 14 John James Jr married Charlotte Frances Dana

at Worfield Church, Salop [Shropshire]

1840 July 6 Charlotte [?]…..born at home [?]

1841 July 20 [?or 14 ?] John Henry [?] born…..died March 3 1842

1842 July 2 a Son stillborn

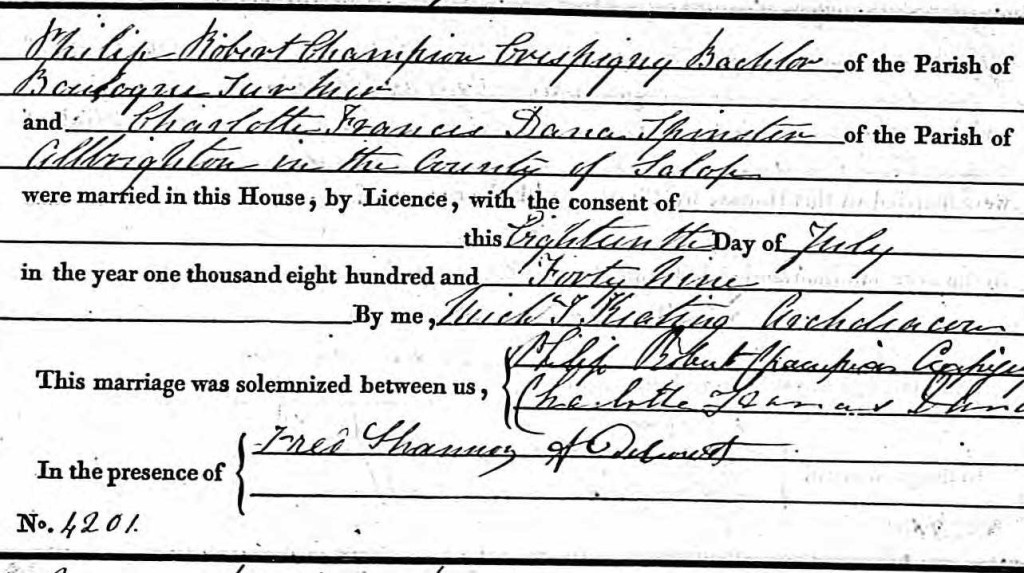

Charlotte Frances Dana first married John James (1808-1855) at Albrighton, Shropshire on 14 May 1839.

The information about the children is confirmed by official records. The British General Register Office holds volumes of lists of births and death for different local offices, arranged in collections of three months, and the birth of Charlotte Constance James was registered at Westbury-on-Severn in the July-September quarter of 1840. In the following year, 1841, the birth of John Henry James was registered at the same office during the July-September quarter, and the death of John Henry James was recorded there in the January-March quarter of 1842. In addition, the parish records of Newnham Saint Peter give the date of his burial as 7 March. Since a stillborn child had legally never lived, no record was required. Of course the mother knew.

The marriage between Charlotte Frances Dana and John James broke down, and in November 1847 Charlotte left her husband and daughter and eloped to France from Ventnor on the Isle of Wight with Philip Champion Crespigny.

John James had engaged a solicitor to pursue his wife and Philip. The solicitor wrote that

… he had used every effort to induce Mr. Crespigny to put in an appearance to an action for crim. con., but without effect. Indeed, whenever he had reason to think that that gentleman might be in England he had sued out a writ. He had sued out at least seven or eight writs, but in no one instance had an appearance been entered.

In February 1849 the divorce went before the Arches Court, the first stage in the proceedings. The Court of Arches was an ecclesiastical court located at Doctors’ Commons in London. It handled the dissolution of a marriage under ecclesiastical law. In the case of James v. James, the court found that the facts were fully established beyond all doubt, and pronounced for the divorce.

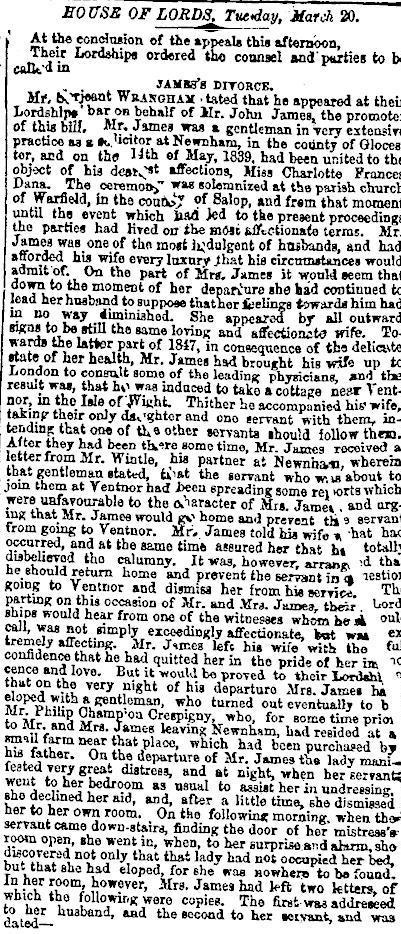

In March 1849 John James brought a bill for divorce before the House of Lords. Among the lords present were the Lord Chancellor, Lord Brougham, Lord Campbell, the Duke of Wellington, Lord Stradbroke, the Earl of Mountcashel, Lord Stanley, the Earl of Suffolk, and Lord Ellenborough.

Parliamentary divorce, divorce by a private act of Parliament, was first used in 1670 and was abolished in 1857 with the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857. Before 1857 three different legal systems applied: canon law, equity law and common law requiring different lawyers and judges and operating in three separate courts. Before 1857 only Parliament could grant a full legal severance of a marriage allowing both spouses to marry again.

The husband of an adulterous wife could take out a civil suit of criminal conversation, or ‘crim. Con.’ in the Court of King’s Bench or Common Pleas to claim damages from his wife’s lover. In 1809 the House of Lords ordered that the transcript of a preliminary trial for criminal conversation should accompany every divorce bill brought before it.

The original object of the crim. con. action had been to punish the seducers of married women and to compensate the latter’s cuckolded husbands. By 1800, the great majority of actions were collusive, and their true function was to provide a legal smoke screen under which both husband and wife could obtain an undefended Parliamentary divorce and remarry.

Philip Crespigny’s refusal to be party to the crim. con. court case was unusual and threatened to derail the divorce action.

With the cost amounting to thousands of pounds, only the very rich could afford a Parliamentary divorce. In the ten years 1841 to 1850 only 43 Parliamentary divorce petitions were brought in England. The decade saw 85 matrimonial cases in the Court of Arches in that decade.

The newspapers of the day reported the divorce of John and Charlotte James in its various stages:

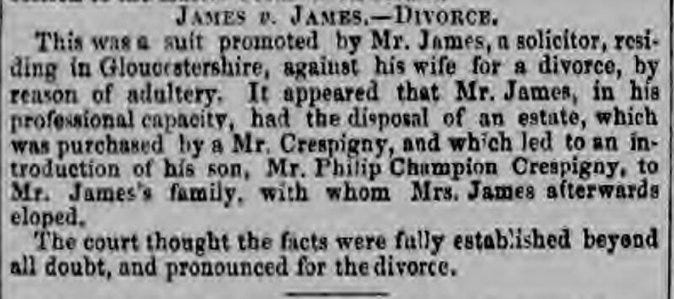

London Daily News, 19 February 1849, pages 6-7, “Arches Court – Saturday”

JAMES v. JAMES. – DIVORCE.

This was a suit promoted by Mr. James, a solicitor, residing in Gloucestershire, against his wife for a divorce, by reason of adultery. It appeared that Mr. James, in his professional capacity, had the disposal of an estate, which was purchased by a Mr. Crespigny, and which led to an introduction of his son, Mr. Philip Champion Crespigny, to Mr. James’s family, with whom Mrs. James afterwards eloped.

The court thought the facts were fully established beyond all doubt, and pronounced for the divorce.

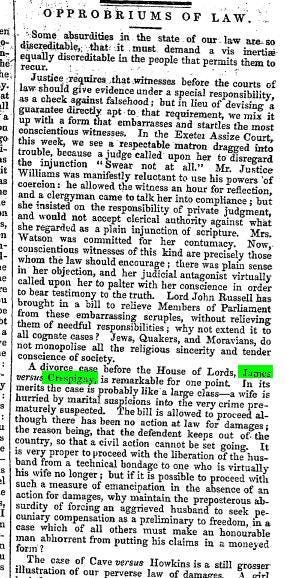

The Hull Packet and East Riding Times (Hull, England), Friday, March 30, 1849; Opprobriums of Law – also appeared in Bell’s New Weekly Messenger 25 March 1849

The Times, 21 March 1849

Letters quoted in the Parliamentary debate include Charlotte’s farewell letter to her husband:

“I cannot live, John, and feel myself a blight upon you and our sweet innocent child…Oh, live to protect and guard our child. She will be a comfort and a blessing to you.”

To her servant she wrote

“Do not be frightened, Estcourt, at my going away. I know you will be kind and good to my darling child. Let her believe I am gone home – though it is to my long and last one. I leave you money (£5), which will pay all till your master comes again. I ask you to be kind and good to the child, and do not let her feel for her poor mother.”

Divorce law at the time required that there should be no evidence of collusion between husband and wife in organising the divorce proceedings. At first sight, the divorce of John and Charlotte James is a model petition for divorce, fulfilling all the requirements: evidence of adultery, including the birth of a child which is not the husband’s; good marital relations up to the time of separation; generous and most affectionate conduct by the husband, even acknowledged by Charlotte’ parting letter; an attempt to pursue Philip Crespigny for criminal conversation damages.

However, it seems likely that for several weeks beforehand, John James, Charlotte, and Philip Crespigny were conspiring in the elopement and the divorce. John James would not have wanted to continue with an adulterous wife and someone else’s child, and everything that happened on the Isle of Wight (where Charlotte Frances James had been staying before her flight to France) and subsequently, must have been arranged in collusion. Whether the witnesses were suborned or simply deceived by the married couple acting a charade is impossible to tell, though we may suspect the number of people aware of the truth would have been kept to a minimum: bribery is one thing, blackmail an unwanted complication.

The weakest point was Charlotte Frances’s farewell letter. She may have intended to confirm the good conduct of her spouse and their mutual affection, but the exaggerated style fitted badly with the events that followed. One feels she should have taken some advice and guidance, though it must be acknowledged that the requirements for a successful petition of divorce – that the husband must have behaved well and there be mutual affection, but that adultery must be proved – are somewhat contradictory.

Philip and Charlotte had been living in a village near St Malo, Brittany. Philip C. Crespigny, rentier [i.e. “of independent means”], accompanied by his Dame [lady: probably not wife, which would be Femme] and their child [described as an Enfant, which would indicate a male child, but which would have been Ada, who had been born on 15 May 1848] were granted a passport for travel to Paris by the local British Vice-Consul at St. Malo on 30 May 1849. The marriage of Charlotte Frances Dana to Philip Champion Crespigny was formalised on 18 July 1849 at the British Embassy in Paris, France.

In 1852, John James also remarried, to Arabella Veronica Dighton. He died in 1855.

Charlotte Constance James never saw her mother again.

Charlotte and Philip had five children, all of whom survived to adulthood. The family emigrated to Victoria, Australia. Charlotte showed no regret for her actions, accepting poverty and hardship in Australia without public complaint.

Clearly my third great grandmother Charlotte tried to hide the evidence of her first marriage by obliterating the details in her Bible. She had been successful to the extent that that part of her story had not been known by her Australian descendants.

Related posts and further reading

De Crespigny, Rafe & Young, Christine Anne. (2020). Charlotte Frances Champion Crespigny Nee Dana (1820-1904) : and her family in Australia

E-book can be viewed http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2899050056

Anniversary of the marriage of Philip Crespigny and Charlotte Dana

Australian arrival of the Champion Crespigny family on the ‘Cambodia’ 31 March 1852

170 years since the Australian arrival of the Crespigny family on the ‘Cambodia’ 31 March 1852

Charlotte Frances Champion Crespigny nee Dana (1820-1904) and her family in Australia

Wikitree:

Post first published at https://anneyoungau.wordpress.com/2024/10/29/charlottes-family-bible/

A great story Anne and well written. An interesting summary on divorce in those days and the documents you uncovered.

My grandmother simply tore the page out of the family Bible that showed my grandfather had been married to her sister. She “never knew how that happened!” Amazing what lengths some of our ancestors went to in order to hide something they did but we can easily find out about it now in documents and newspapers.